SSSIMPLY BAHAMIAN

Snakes are probably the most fascinating group of the 12,502 living species of reptiles on earth. As of September 2025, the Reptile Database recognized 4,203 species of snakes, representing over a third of all living reptile species.

Snakes are some of the most amazing predators on earth, coming in a wide range of colours and sizes, from a few centimetres to over 10m (33ft) in length.The Bahamas has moderate snake diversity with 12 species

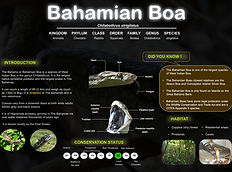

Bahama or Bahamian Boa

naturally occurring in the country, representing five families (Boidae, Tropidophidae, Dipsadidae, Typhlopidae, Leptotyphlopidae).

Bahamian Boas mating

Boas

The Family Boidae, is represented by 69 species of small to gigantic non venomous, constricting snakes found on most continents except Antarctica and Australia. Boas are sometimes confused with Pythons and both possess some similar features such as vestigial pelvic girdles, two functional lungs, and infra red detecting pits in the labial scales. However, there are some important differences. Firstly, Boas are found around the world whereas pythons are restricted to the “Old World” (Africa, Australia and Asia).

Secondly, although both boas and pythons have labial pits, boas have pits between labial scales whereas pythons have pits within the labial scales. Most Boas, also have live birth whereas Pythons lay eggs.

The sub-family Boinae is the group that includes most species of “true boas” which includes the largest species of snake on earth, the Northern Green Anaconda. There are five genera in this subfamily but the genera of interest to us is the West Indian Boas in the genus “Chilabothrus”. This genus is also endemic to the West Indies and consists of 14 extant (living) species found on the islands of the Greater Antilles, The Lucayan Archipelago, and the Virgin Islands. The name “Chilabothrus” means “lips without pits” and is a feature seen in most species in this genus. This genus also includes the largest snake in the West Indies, the Cuban Boa (Chilabothrus anguilifer). The Cuban Boa is also the most basal of the genus Chilabothrus and the only species that retains its labial pits. The Bahamas is home to the most species of West Indian Boas in the genus, with five known species.

Bahamian Boa

The ancestors of Chilabothrus came from South America and the genus is believed to have formed about 30.2 million years ago (mya). The southern Bahama boa separated from their Hispaniolan ancestors during the Pliocene. Our Bahamian boas can trace their ancestry to Hispaniola, where our Bahamian Boa group diverged from the Hispaniolan Boa during the Pleistocene. Also, during the Pleistocene the Abaco Boa (Chilabothrus exsul) and the Bahama Boa (Chilabothrus strigilatus) diverged from each other about 1.8mya. Genetic research also

indicates that the eastern Great Bahama Bank boas (GBB) diverged from the Western GBB boas about 35 thousand years ago (kya).

Bahamian Boas show interesting degrees of island dwarfism and gigantism with our smallest boas being less than 1meter long, and our largest reaching lengths of about 2.4m (8ft). However, unlike other boa species which have large, thick bodies, our boas are rather slender, a trait that can be attributed to food resources. Unlike the island of Cuba, The Bahamas is not known to have large native mammals. Birds, Rock Iguanas and Hutias are the only large extant animals in The Bahamas and because of smaller size food resources, our boas retained a rather slender size.

All Bahamian Boa species are found on their own individual banks (i.e. they do not coexist with other boa species). For example, the Abaco Boa is endemic to Abaco (Little Bahama Bank), the Bahama Boa is endemic to the islands of the Great Bahama Bank, the Silver Boa is found on the Conception Island Bank, and the Crooked/ Acklins Boa is found on the Crooked/Acklins Bank.

Breeding season for Bahama Boas begins in February with a gestation period of 5-6 months. Babies are born live. Peek season for seeing baby boas range from September to November. Boas usually breed once every two years. Baby boas feed on lizards and frogs before graduating to mammals and birds when they reach adulthood. There has also been recorded cases of cannibalistic and predation on other snakes like the Bahamian Racer in captivity as well as an attempted predation on a Bahamian Racer in the wild.

The snake family Colubridae contains 2150 species of snakes of various sizes and ecology. Within this family is the subfamily Dipsidinae which consists of West Indian Racer snakes. Within this family is the genus Cubophis (Cuban Snakes) which is represented by six species of opisthogliphous (rear-fanged) snakes, one of which is found in The Bahamas. These snakes are slender, fast moving, diurnal active hunters with broad diets consisting of lizards, frogs, other snakes, small birds and rodents. People sometimes confuse them with cobras because they sometimes flatten out their throats and raise their heads when they feel threatened. Scientists believe that the ancestors of West Indian Racers came to region from South America during

Racers

Bahamian Racer showing "hood"

the Miocene, arriving in the Greater Antilles before eventually dispersing to other islands like The Lucayan Archipelago, and Cayman Islands during the Pliocene and Pleistocene Epochs.

Bahamian Racer (juvenile)

The Bahamian Racer (Cubophis vudii) is the only native species of Racer snake known to inhabit The Bahamas. However other racers were recorded from The Bahamas including a Cuban Racer (C. cantherigerus, found on the Cay Sal Bank) and the remains of a Hispaniolan Lesser Racer (Hypsirhynchus parvifrons) found on Little Inagua). These snakes, however, are generally considered vagrants, not established species in the country and therefore not part of the native snake fauna of The Bahamas. The Bahamian racer is found on most islands in The Bahamas except San Salvador and Mayaguana and reaches a length of 1.2m (4ft). Like the Bahamian Boas breeding season for Bahamian Racers begins in February with a gestation period of 2 months before eggs are laid. The eggs usually hatch after 2 months.

Tropes

The Family Tropidophiidae is represented by 37 species small to medium sized non-venomous constricting snakes found in Central and South America and the West Indies. This group of

Bahama Trope (adult)

Based on phylogenetic research, Tropes are believed to have originated from the Andean region of South America. The ancestor of the Tropidophiid group later dispersed into the Caribbean Region from northern South America in the late Eocene. Once in the Caribbean, namely the Greater Antilles, rapid speciation occurred along with dispersal to other West Indian islands, like The Lucayan Archipelago.We have two endemic species of Tropes in The Bahamas: The Bahama Trope (Tropidophis curtus) and the Inagua Trope (T. canus). They are small animals, reaching lengths of 41cm and feed on lizards and frogs.

Bahama Trope (juvenile)

snakes are known by several names including Tropes, dwarf boas, Thunder Snakes, Shame Snakes, and Pygmy Boas. Most species occur in the Wes Indies with Cuba having the greatest diversity (17 species). In The Bahamas, Tropes are sometimes confused with rattlesnakes based on their pattern and the orange or black tip of their tails. When they feel threatened, they often curl up into balls or bleed from their eyes or mouth, a behaviour known as auto-hemorrhaging. They are nocturnal in habit and feed on lizards and frogs. They also undergo an ontogenetic colour change, changing from light colored as juveniles to dark colored as adults.

Blind Snakes

Typhlopidae is a large family consisting of 283 species of subterranean snakes commonly known as blind snakes or worm snakes. Worm snakes have a cosmopolitan distribution and are closely related to thread snakes. These snakes feed on both ants and termites and their larvae. There are 43 species of Blind snakes in the West Indies, three of which are found in and are endemic to The Bahamas: The Bahama Slender Blind snake (Cubatyphlops biminiensis), Earthworm Blind snake (Typhlops lumbricalis), and Inagua Blind snake (Cubatyphlops paradoxus).

Bahama Slender Blindsnake

Like the family Typhlopidae, the Leptotyphlopidae (Threadsnakes) is a large family (144 species) of subterranean snakes with a broad distribution, being found in Africa, the Americas, the West Indies, Arabia and Southwest Asia. Threadsnakes differ from Blindsnakes in that they have teeth only in their lower jaw, whereas blind snakes have teeth in both the upper and lower jaws. Phylogenetic studies on this family indicate that they are an ancient group who can trace their origins into the Cretaceous Period and that they diverged from Blindsnakes during the same period. The group later dispersed and arrived in the "New World" (South America) from Africa in the Late Cretaceous. Like Blindsnakes, Threadsnakes feed on ants, termites and their larvae. The Bahamas is home to one species, the San Salvador Threadsnake (Epictia columbi) which is endemic to San Salvador.

Earthworm Blindsnake

Most of the native snakes found here are endemic to the country. No snake in The Bahamas is dangerous to humans, so no need to worry when one is encountered in the wild. Nevertheless, if you encounter one at your home or general daily activities, we do encourage you to please show them respect and leave them alone!

posters

The Bahamas is home to 12 native snake species, including five boa constrictors, two pygmy boas (tropes), three blindsnakes, one threadsnake, and the Bahamian Racer. These snakes inhabit diverse environments, from pinelands to residential areas. The Bahama Boa, the largest native terrestrial carnivore, can grow up to 2.3 meters (8 feet) long and weigh over 13 pounds. The Bahamian Racer is the only venomous species, with a weak venom that affects small prey like lizards and frogs. Blindsnakes live mostly underground, feeding on ants and termites, while the pygmy boas, small constrictors, feed on lizards and frogs. Bahamian snakes are often misunderstood and persecuted, with many people choosing to kill them on sight, despite the fact that they are harmless to humans and would rather flee than fight. These snakes play a vital role in controlling populations of disease-carrying pests like rodents. Encountering a Bahamian snake should not lead to harm; instead, people are encouraged to leave them alone or contact a professional for safe removal. These native snakes are valuable to the Bahamian ecosystem and deserve protection and respect.

The Bahamian Racer, also known as the Brown Racer or Garden Snake, is a medium-sized, fast-moving snake endemic to The Bahamas, reaching up to 1.21 meters (4 feet) in length. It is found throughout the country, except in San Salvador and Mayaguana, and has five subspecies, including the Northern Bahama Racer and Inagua Racer. The snake exhibits polymorphism, coming in various colors and patterns that help with camouflage. It feeds on birds, reptiles, frogs, and even other snakes, including its own kind, and is also known to scavenge. The Bahamian Racer is the only venomous snake in The Bahamas, but its mild venom is harmless to humans and only affects its prey. The Bahamian Racer breeds as early as February, with eggs laid two months after mating and neonates hatching two months later. The species displays sexual dimorphism, where males have longer tails, and females have longer bodies. When threatened, the snake flattens its throat, resembling a hood, which leads some to mistakenly identify it as a cobra. Despite this defensive behavior, the Bahamian Racer is harmless to humans and prefers to flee rather than attack, underscoring its non-aggressive nature.

The Bahamian Racer has a broad distribution across The Bahamas and there are five subspecies four of which are shown in this poster. This common snake comes in a variety of different colours. Some researchers think that some subspecies may actually be different species. More research into this species is needed to determine if the Bahamian Racer is a cryptic species

West Indian boas are a unique group of non-venomous snakes endemic to the West Indies, with 14 species, most of which are found in The Bahamas and Hispaniola. These boas hunt by constriction, primarily at night, feeding on animals like lizards, birds, and rodents. The Cuban Boa, the largest West Indian boa, can grow up to 6 meters (19.8 feet) and has heat-sensitive pits to detect prey, while the smallest is the Hispaniolan Vine Boa, reaching only 27 inches. The Bahamas is home to more species of West Indian boas than any other country, with five species, including the Bahama Boa, which can grow over 2.3 meters (8 feet), and the recently discovered Conception Island Boa, measuring just 30 inches. Despite their ecological importance, Bahamian boas are among the most persecuted animals in the country, often killed due to fear and misunderstanding. These boas are harmless to humans and play a vital role in controlling populations of disease-carrying vermin like rats. They generally avoid human contact but may hide in sheds, roofs, or vehicles, particularly during colder months. Fortunately, growing awareness and education efforts have led to a shift in public perception, with more people choosing to safely relocate rather than harm these snakes. However, stronger legal protections for boas and other snakes are still needed to ensure their conservation in The Bahamas.

photo gallery

|  |  |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |  |

|  |

resources

Adalsteinsson, S.A., Branch, W.R., Trape, S., Vitt, L.J. and Hedges, S.B., 2009. Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of snakes of the Family Leptotyphlopidae (Reptilia, Squamata). Zootaxa, 2244(1), pp.1-50.

Hedges, S.B., Couloux, A. and Vidal, N., 2009. Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae). Zootaxa, 2067(1), pp.1-28.

Johnson, S., 2021. Attempted predation of a Bahamian Racer (Cubophis vudii vudii) by a Bahamian Boa (Chilabothrus strigilatus strigilatus) on New Providence, The Bahamas. Reptiles & Amphibians, 28(1), pp.59-60.

Krysko, K.L., Steadman, D.W., Nunez, L.P. and Lee, D.S., 2015. Molecular phylogeny of Caribbean dipsadid (Xenodontinae: Alsophiini) snakes, including identification of the first record from the Cay Sal Bank, The Bahamas. Zootaxa, 4028(3), pp.441-450.

Reynolds, R., Henderson, R., Diaz, L., Rodríguez Cabrera, T, & Puente-Rolón, A. 2023. Boas of the West Indies: Evolution, Natural History, and Conservation.

Schettino, L.R., Mancina, C.A. and González, V.R., 2013. Reptiles of Cuba: Checklist and geographic distributions.

Schwartz, A. and Henderson, R.W., 1991. Amphibians and reptiles of the West Indies: descriptions, distributions, and natural history.

Uetz, P., Freed, P, Aguilar, R., Reyes, F., Kudera, J. & Hošek, J. (eds.) 2025. The Reptile Database, http://www.reptile-database.org, accessed [January 7 2025].

Zaher, H., Trusz, C., Koch, C., Entiauspe-Neto, O.M., Battilana, J. and Grazziotin, F.G., 2024. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the dwarf boas of the family Tropidophiidae (Serpentes: Alethinophidia). Systematics and Biodiversity, 22(1), p.2319289